I have yet to knowingly meet someone who's never tried chocolate. In fact, I can count on one hand the number of people who have had allergies or a genuine dislike of quality chocolate. Since I'm a certified chocolate maker, that might lead you to believe that chocolate is universally known and recognizable— but is it really? Do YOU know what goes into a chocolate bar?

Jump To

Is Chocolate Different in Other Countries?

Depending on where you come from, the chocolate you grew up with is indeed different from what someone else may have known as "chocolate." In Mexico and Central America, unsweetened chocolate is often consumed as part of savoury traditional dishes, while in the Philippines it's featured in a bittersweet chocolate beverage called tableya.

Throughout the dozens of countries in which the raw material of chocolate (a fruit called cacao) is cultivated, there are dozens more ways in which the fruit, its juice, and the transformed cacao beans have been consumed over the years. Now there's even a chocolate sweetened with cacao sugar.

Modern globalization is changing this, with cheap chocolate now prevalent everywhere. But despite this rampant globalization, there are still regional differences in chocolate. For example, even milk chocolate is different in Europe from what we grow up with in The US.

A company most young American associate with sugar comas on Halloween, Hershey's is often hated in Europe. But why do Europeans hate Hershey? It's all in the milk powder.

The company uses a more sour milk powder, containing a higher concentration of butyric acid, which both differentiates them from the competition and confuses visiting chocoholics. In addition, different companies use different percentages of cacao and chemical preservatives.

Even the inclusions they put in their chocolate vary, with Europeans tending towards nuts and dried fruits, while Americans prefer caramels and mint chocolates.

It's honestly a toss up as to whether giving farmers a taste of some of this cheap, over-processed chocolate is better than never giving them a taste at all. Because yes, there are chocolate farmers in the world. Cacao, also known as cocoa, is a fruit grown around the equator in largely poor countries (though not always).

The end product we call chocolate tastes more of sugar than of cocoa, and is not representative of the delicate flavor potential which craft chocolate makers are working on promoting. Chocolate still has a long way to go.

Commercial chocolate doesn't give cocoa producers a taste of what they could contribute to; it only tells them what has already been established. But this is not to say that the chocolate making process around the world is wrong. Far from it.

Over the last several centuries, the world has been experimenting with various chocolate recipes, many with great success. We even invented new words for the chocolate fruit: cocoa and cacao.

The difference between cocoa and cacao is a mere triviality, cocoa being the English & French word for the original Spanish of cacao. Cacao itself was stolen from a Nahuatl word, but that's another, much longer story to get into. We have some chocolate to make.

What Does Percentage Mean in Chocolate?

The simplest (and least sweet) chocolate is made with just cacao, but most people find it inedible. Almost all chocolate also includes a sweetener. This better allows the beans' inherent flavors to be expressed and focused on when tasting.

Most "chocolates" are unfortunately also loaded down with chemical emulsifiers, vegetable oils, and much more sugar than necessary. This means that chocolate as a whole is seen as a vehicle for sugar, which is often the real culprit behind distaste for the commercial stuff.

Bars of this cheap chocolate are most people's introduction to cacao. But my goal is to remind people of the flavorful value lying behind the sugar. The main player in any bar of quality chocolate tasted on this site is going to be the cacao.

The percentage given on the wrapper of a chocolate bar is how much of the bar comes from cacao, as fat and solids. So this page explains the steps followed to make dark chocolate, using just cacao and sugar and cocoa butter (if the maker so chooses).

When I make chocolate at home, I complete steps 6 through 12. I usually start with just 2kg of unroasted cacao beans, but it still takes me about a month to make one batch from start to finish. The complete, simplified 12 steps to making chocolate from tree to bar are described in-depth below.

Chocolate Making from Tree to Bar

1. Cultivation

To cultivate cacao is a years-long process, and true to the circle of life, one must start with a fresh cacao seed or a tree viable for grafting. Recently many farmers are turning to grafting higher-quality cacao varietals onto existing higher-yield trees in the hopes of creating high quality and high-yield trees.

But to make a single cacao tree seedling from fresh beans, one to three beans are taken from a fresh pod (less than 5 days old), and then put into a hot wet place to germinate. Once that root is formed, the seeds are put into a bag of nutrient-rich earth, root side down, and lightly covered in soil.

A couple of weeks later or so later you see the tiny baby tree growing, with the once-purple or white bean now brown and cracked all over, as the germinated insides become a whole new being. Because cacao needs to be kept in a hot, wet climate, cacao only grows within 20 degrees of the equator, with few exceptions.

2. Collection

The tree lives a shadowy-but-sunny two to five more years of childhood, and then the tree begins to bear fruit on the branches where it gets enough sun. The football-shaped fruits emerge from tiny flowers which grow all over the tree. These flower are pollinated by flies called midges, so minuscule that the naked eye cannot see them.

Ten varieties of cacao are currently known to exist: Marañon, Curaray, Criollo, Iquitos, Nanay, Contamana, Amelonado, Purús, Nacional, and Guiana. These are are often referred to by their grander types: Criollo, Trinitario, Forastero, and Nacional.

Temperature, rainfall, altitude, surrounding foliage, and amount of sunlight can all affect the final flavor & fat content of beans. Farmers collect pods from trees once they are ripe, usually indicated by a large change in color. The pods seen in the Wonka Movie trailer are these same cacao pods.

Pods can be most any color, with the largest different between criollo (fine flavor) and forastero (bulk cacao) being in their shapes. Cut off by machetes when ripe, pods are gathered together and then opened by those same machetes, and the seeds are scooped out by hand and set in a large pile.

3. Fermentation

After the seeds— usually thereafter called beans— are removed from their pods, they undergo fermentation. This process is traditionally done in wooden boxes placed in the sun and then covered in banana leaves so that the temperature gets high enough.

During fermentation, core temperature of the bean pile easily exceeds 40 degrees Celsius, and the bitter beans lose some of their bite as chocolate flavor pre-cursors are formed within each seed. The acids and alcohols being created as the sugars ferment, interacting with yeast and bacteria in the boxes, give off a strong odor.

Beans in mid-fermentation remind me of a sweet chardonnay, while over-fermented beans will start to smell like paint thinner and become grey inside. The color changes from a vibrant purple (forastero) or white (criollo) to a deep brown or light brown color, respectively.

Farmers periodically mix beans to ensure even fermentation, and cut a random sample of beans open to test that everything is going well. After 2 to 7 days of fermentation, the length of which depends upon bean type and the climate (criollos usually ferment in 2-3 days), the beans have lost about half their weight and taste much more palatable.

4. Drying

Following fermentation, the beans are laid out to dry. It takes 5 to 10 days on average for beans to dry enough to be shipped. In some very wet climates, such as Papua New Guinea or Trinidad, wood fires can be used to dry the beans fully, leading to a smoky flavor in the beans.

If they are not fully dried, not only can mold form during shipment, but the flavor of the beans is very acidic and unpalatable. The flavors formed during fermentation continue to change during drying, making this a critical step in flavor development.

After drying, the beans are in the domain of the chocolate maker, almost always a different person from the cacao farmer.

5. Shipment

If the farmer is part of a cooperative, then all of their dried beans will be sent to a centralized building to be prepared for shipment. Cacao is put into massive sacks, usually made of jute, holding around 60kg of cacao each.

The jute bags are then sent to middlemen to distribute in their region, or sometimes directly to the chocolate maker.

6. Sorting

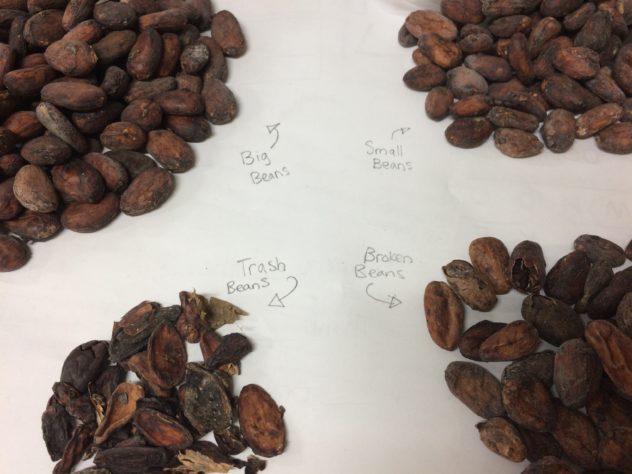

Once received, the maker & his or her minions must sort the beans to remove any rocks or dirt or insects (much worse has been found, but these are the most common things). Any cracked or broken beans should also be taken out. Additionally, some shipments are varied enough to warrant sorting by size of beans.

7. Roasting

Once all cleaned up, the beans are roasted, sometimes in small batches of a few pounds and sometimes hundreds of pounds at once. Usually a maker will try a few roast profiles before settling on just one for the whole shipment, because temperature and length of roast both play huge roles in which flavors are apparent in the final product.

Those flavor pre-cursors and acids formed during fermentation come back into play during roasting. The chemical composition of the beans changes drastically at this point, and that "chocolatey" flavor you associate with chocolate is finished up forming here— though there are more steps which impact other flavor notes down the line.

8. Cracking & Winnowing

The beans must next be winnowed, meaning that their thin outer husks are removed, usually in the process breaking them into smaller pieces called nibs. Some very small batches of roasted beans can be cracked and their shell peeled off by hand.

At home, I take a hammer to the beans I toast in my 1-pound coffee roaster, and then put them in a bowl and blow away the shells with a hair drier. Larger batches of cacao must go through a machine which runs air under the beans, forcing the heavier beans into one container and the lighter husks into another.

These husks generally account for about 20% of the weight of the beans, and though some makers brew the shells like tea, others sell them to local gardens as mulch.

9. Grinding

Once they have the nibs all clean, makers must grind them to get that smooth texture we all crave. To grind the cacao, makers generally use either stone or metal grinders. Stone grinders are sometimes seen as preferable because they add less of a flavor to the chocolate during processing.

Some small-batch or old fashioned makers use hand crank-operated grinders, a much slower but often cheaper option. Sugar must also be pre-ground if the machine is not powerful enough to quickly grind it on its own (as with small home chocolate machines).

The Champion Juicer is a common pre-grinder used in micro-batch chocolate making. You must also heat the nibs before adding, if you've got them to a small enough size without much grinding.

10. Conching/Refining

To conche & refine chocolate is to allow the mixture to be pulverized into the smallest possible particles. This emulsifies the cocoa solids and the cocoa butter, softening the cacao's flavor and smoothing out overall texture.

For a milk chocolate, the maker would also add the powdered milk around this time, having added the extra cocoa butter required for good milk chocolate when they initially added the cacao (and sugar).

To be more specific, refining refers to particle size, while conching is a less-definable process during which the sharp flavors in chocolate are reduced. The process of conching can take anywhere from 6 to 72 hours, and this largely depends on machine size, which larger machines being able to heat up and complete the process more quickly.

During the conching, a melangeur (French for "mixer"), continually mixes the chocolate to release bad flavors in the form of the acids built up during fermentation. To conche is basically to introduce air into the chocolate, with the idea that it allows these sour and bitter volatile particles to evaporate, softening the overall flavor of the chocolate.

11. Tempering

Finally, the chocolate tastes like chocolate should (hopefully), and it is ready for tempering. One of the more chemically-intense steps of chocolate making at home, is this heating & cooling process. Basically, tempering stabilizes the fat molecules in chocolate.

Of the six crystal structures which the fat (cocoa butter) can form, Form V is the most stable. Getting all the cocoa butter to form enough of these Form V particles is crucial to getting chocolate glossy and durable, melting in your mouth rather than your hands.

Tempering involves heating chocolate to about 115 degrees Fahrenheit (less for milk or white or ruby chocolates), cooling to about 84 degrees (again, less for milk or white chocolates), and then turning it into bars or truffles.

Careful not to bring it above 90 degrees, or it will then go "out of temper," chocolate makers must be especially watchful at this phase. When the cocoa butter is stable, it is less likely to have bloom, that greyish look some bars take on as cocoa butter rises to the surface.

Creations such as ganaches and frostings do not need to be tempered; there are many other ingredients affecting the appearance and texture at that point. Other ingredients in those desserts will prevent the formation of bloom, and reduce the chance that they will sit around long enough for it to form.

12. Molding & Packaging

To mold bars into plastic or silicone molds is the final step, though sometimes skipped in favor of making truffles or some other delectable treat. Tempered chocolate should be lightly tapped against a tabletop to release air bubbles after molding.

Bars will take a few hours to fully set, and then they should be shiny and have a strong snap when broken. Packaging on bars ranges from aluminum or plastic sealed packets to ziplock containers or paper wrappers.

How Is Chocolate Made From Tree to Bar (Pictures)

If you found this guide to how chocolate is made helpful, please pin it!

Leave a Reply