Japan's quietly growing craft chocolate scene is a direct contrast to the futuristic image it projects. The country's had an astounding number of chocolate makers set up shop over the last half decade, but most of them are in cities & settings we haven't heard of: Onomichi, Kitakyushu, Niigata, Iizuka.

There are a fair number in Osaka and Tokyo, of course, but they are no longer the majority. Thanks to the power of both social media and chocolate festivals, the makers from much more rural parts of Japan finally have the chance to shine and show off their wares across the country as well as abroad.

One of those makers is Cacaoken, a family-owned company based in Iizuka. Recently I sat down to chat with one of Cacaoken's owners, Yukari Nakano, about craft chocolate culture in Japan, and how its arrival overturned Japan's perception of chocolate far beyond the skyscrapers of Tokyo.

A small city in one of Japan's southernmost prefectures, Iizuka is just an hour outside of Fukuoka City, and offers a stunning backdrop for the small chocolate factory. From the mountains popping up in the background to the rice fields on either side of the highway, this is more like the backdrop I'd look for when cycling through Japan, not looking for an award-winning chocolaterie. As the only chocolate maker in the city, one might expect Cacaoken's presence to be highly celebrated, but their quiet shop is located on a side street off the main drag, and it looks ready to move at any moment.

Move in a literal since, because it's a trailer.

The small, bright red trailer is space enough to house their entire collection of goods, however, and is connected to a small area with a bathroom along with their minuscule chocolate factory. When I walked up to the shop, two older gentlemen were sitting at a small table in front of the shop, and surprisingly, they greeted me in English. I thought nothing of it until I'd been browsing for a bit, taken some pictures, and realized that the woman behind the counter couldn't understand a word I'd said.

But, she had kind eyes, so I persisted. I spoke in Korean & hand gestures, and she responded in Japanese & body language. Then she handed me a cup of coffee, and I accepted with a small bow. What I hadn't yet realized was that she was the last piece of the puzzle, the third family member that makes up the life force of Cacaoken.

Her name is Fumiko, and she is a chocolate maker.

Along with her husband (Toshimi), whom I'd greeted outside, and her daughter (Yukari), whom I'd met at an event months earlier, Fumiko is part of Japan's growing grid of rural chocolate makers. She's also part of the rare breed of female chocolate makers, and her family is the team behind one of Japan's older chocolate makers, Cacaoken. The first seed of chocolate making was planted in their heads back in 2012, when they read an article in a Japanese magazine that talked about an American bean to bar chocolate maker.

It piqued their interest. Before they opened up shop in Iizuka, Fumiko & Toshimi managed an industrial candy company. Their daughter Yukari, whom I interviewed, says of the family "we knew about industrial chocolate, but we didn't know about bean to bar chocolate."

So when they finally got to taste bean to bar chocolate, made by a small Japanese maker in Tokyo, her parents knew immediately that they wanted to open a shop of their own. The flavors were so distinct and different from what they'd been tasting for decades that they knew they'd stumbled upon something unique. Yukari took a bit more convincing, but eventually she got on board. She speaks fluent English, so she's become the company's spokesperson at most of the chocolate shows around Japan. She's even been the force behind a recent collaboration they've been doing with the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which is doing a special tasting menu using their cacao sauce until December 26th, 2018.

One of those Japanese chocolate shows is where I first encountered her & her chocolate, at the Osaka Salon du Chocolat. Her diverse range of products, from cacao fruit wine and honey with cocoa nibs to her line of bars and bonbons, has an uncommon blend of cultures. The mix of Japanese, Vietnamese, and American influence made me curious enough to travel to Fukuoka several months later and check out her shop. Imagine my surprise when I realized how strikingly small the setup is. If you've never ventured out of the well-designed cafes of Tokyo, then you'd be startled at the shop's sudden appearance.

"When we first started making chocolate a few years ago, there were only maybe 10 to 20 makers in Japan; now there are a hundred or more" [all across the country].

Just as single origin drip coffees and fancy cafes suddenly popped up even in the Japanese countryside, so did bean to bar chocolate find its way out of the cities. While the Nakano family started their mini-chocolate factory in 2014, just a few years ago a large company made a big push to educate the public on what is "real chocolate," meaning bean to bar chocolate. So by Yukari's estimates about 10% of the population knows the basic meaning of the phrase "bean to bar."

It was around the time of this manufactured "bean to bar" chocolate, in 2016, that craft chocolate became trendy in Japan. It was only a matter of time before people started looking for non-corporate bean to bar options, which is when home makers really started coming out of the woodwork.

Thanks seemingly in part to the American influence upon Japan, this widespread abuse of the concept behind "bean to bar" actually might have been the impetus for home chocolate makers' sudden multiplication. This is when many Japanese people realized that not only is there better chocolate out there, but they could make it themselves. On top of that, about two years ago journals and popular television shows started explaining how chocolate is made. Their programs focused on the flavors of unique bean origins rather than specific chocolate making or tempering techniques, as previous chocolate-focused episodes had.

Starting as early as last year, Yukari also noticed a marked shift from the previous obsession with European chocolatiers and flavors. Consumers are now more fascinated with Japanese chocolatiers and ingredients, and along with it, Japanese bean to bar. "Now I think bean to bar chocolate is not so difficult to start to make," she remarks. This is in reference merely to access to equipment, she clarified, but goes on to point out that chocolate making can be quite an isolating job. It tends to attract some peculiar personalities compared to the more popular choice to become a chocolatier.

Yet a new chocolatier has to consider their business model when they're setting up shop. They need to sell bonbons fresh and preferably direct-to-customer, unlike bars of chocolate which are comparably easier to transport. So they usually go to a big city to set up shop; no local customers equals no business.

But if you're a bit more of a recluse, or have a particular passion you want to combine with chocolate, then it makes more sense to set up wherever there's cheaper rent. You can quietly perfect your craft at a relatively low cost, and slowly educate the community around you. Take the Nakano family's setup, for instance. Their small trailer is located off the main road in a small city, easily accessibly by public transportation, but more or less set up in a parking lot. Yet they've built up a reputation over the years by selling at chocolate festivals throughout Japan, and are now able to sell both direct to consumer and in retail shops across the country.

"I think the first year, second year it's very difficult to sell to the local people," she laughs. "But if they compare the taste of the chocolate, they suddenly really easily understand how different it is. So this thing is really easy to teach to the customer."

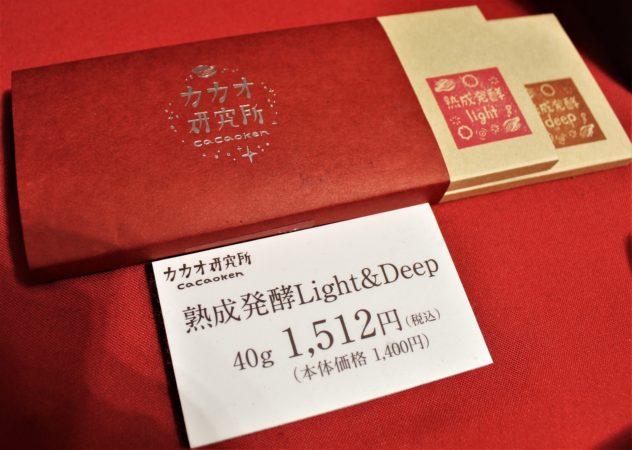

The Nakanos currently use cacao sourced from Ghana, Peru, Haiti, and Vietnam, so they have a very clear contrast of flavors at their disposal. But they also make a variety of confections highlighting Japanese traditional flavors and ingredients, like their nib-specked raw sugar squares or shiso milk chocolate, and have a clear focus on sharing the stories of the origins, as well.

Like most Japanese makers, they follow the American method of two-ingredient dark chocolate, though they also craft a 40% white chocolate, uncommon in East Asia. To make their milk chocolate, they actually blend the white and the dark to the desired percentage, using mostly the Vietnamese beans they source directly from farmers. Although a Japanese importer brings in their other origins, Cacaoken does their best to differentiate themselves from other makers.

They've made it their mission to not just educate their own community on chocolate, but to spread the learning abroad to foster connection at the source of their cacao, in southern Vietnam. There's nothing wrong with buying your cacao from an importer, which is what most Japanese makers do, but the Nakanos just see their future shaping up differently. The farmers they work with in Vietnam continue to inspire them to build up their business and create value, every day. It's more than just making the product and selling it, as any small business owner would tell you.

It's about teaching young children about chocolate making and other cultures. It's seeing the delight of rediscovery on an adult's face. It's sharing love of community and love of food, and it's priceless.

It's such a unique problem, figuring out how to be a chocolate maker on a small scale and still make money for yourself and those who depend on you. The same questions likely both plague and intrigue the family each and every day. How do you make interesting products? How do you use your limited resources to market those products? Is it possible to create a customer base purely through education? But even when it's tough, there's always something more to do, more they can do.

Cacaoken relishes this opportunity to not only make great chocolate, but also educate their community on how chocolate is made and introduce them to other cultures through chocolate & cacao. Just as they honor their own Japanese culture through their chocolate, they seek to also share the stories of the places from which they source their beans, and to use chocolate as their medium of choice.

When I first met Fumiko she was preparing to teach a class on chocolate making to a local middle school, tasting and comparison included. Since she doesn't speak English, she takes on a lot of the local education work. But she also has big plans for their Fukuoka shop, while Toshimi continues to expand the impact of their cafe in Vietnam, bringing both locations into the future with various technologies that they're not quite ready to reveal.

So let's just say that the Nakanos see the future, and it's very connected.

To order any of the family's chocolate bars or cacao products, you can check out their website here and buy internationally from Cocoa Runners (when in stock). The Tokyo Imperial Hotel buffet featuring their cacao sauce runs until December 26th, 2018.

Cacaoken Locations

Address in Japan: 17-79 Higashitokuzen, Iizuka-shi, Fukuoka-ken 820-0032, Japan

Address in Vietnam: Vietnam, Lâm Đồng, Thành phố Đà Lạt, ラムドン

Pin me!

Emily

What an incredible story! So interesting that they're using cacao from Vietnam—I recently lived in Hanoi and ate a lot of Maison Marou chocolate (Vietnam's first boutique chocolate brand). I'm often surprised to learn what countries have a chocolate culture!

Max

I've found that all countries have a chocolate culture if you look closely enough! I'm glad you liked the interview, Emily, and I hope you find some quality chocolate wherever you're living now, as well. Marou makes some delicious bars; I wrote about them earlier this year when I was in Saigon, and I'm glad you had the chance to frequent their chocolate house!

Dagney

Fascinating and beautifully written! Thank you for sharing this experience. I learned so much!

Max

Thanks, Dagney! I'm glad you got to learn more about Japanese chocolate culture, and I hope it inspired you to check out some of it when you visit Japan!! 😀