People often remark that Filipinos and Mexicans have a lot in common, and this isn't pure coincidence. From cuisine and Catholicism to a parallel colonial history, these shared traits extend to chocolate. Or rather, a lack thereof.

For an audio version of this story, click here.

Jump To

Spanish Colonization of The Philippines

The story of chocolate in the Philippines starts roughly a century-and-a-half after the arrival of the Spanish, which you can read more about here. Over those first 100+ years, the Spanish spread both a system of colonial taxes and the Catholic religion (though they were never wholly successful with the latter). But the large-scale rule of Catholicism in Las Filipinas— as the islands were known— is important because the Spanish priests and friars had direct connections with the Filipino people, including through language.

Filipino as a language is only a little over 70 years old, and still not fully accepted, even today. So imagine the hundreds of languages spoken in the Philippines of 400+ years ago, how much power local priests must have had by being able to communicate in some of them. Additionally, those who were high up in Spain's Catholic hierarchy had control over much of the agricultural land from which the Crown's taxes were paid, including the land on which cacao was cultivated.

Back then, the Spanish more or less hand-picked which crops would be cultivated on those lands, based on what crops they wanted to collect as tribute. One of those choices was cacao.

History Of Chocolate In The Philippines

Cacao cannot grow in Spain, with the possible future exception of the Canary Island. So if the Spanish wanted to keep consuming chocolate, they needed to receive the beans as tributes of sorts from their various colonies. In a way, cacao was also the perfect tribute. If it was handled well, it would store well for years, fine for the months-long journey back to Europe.

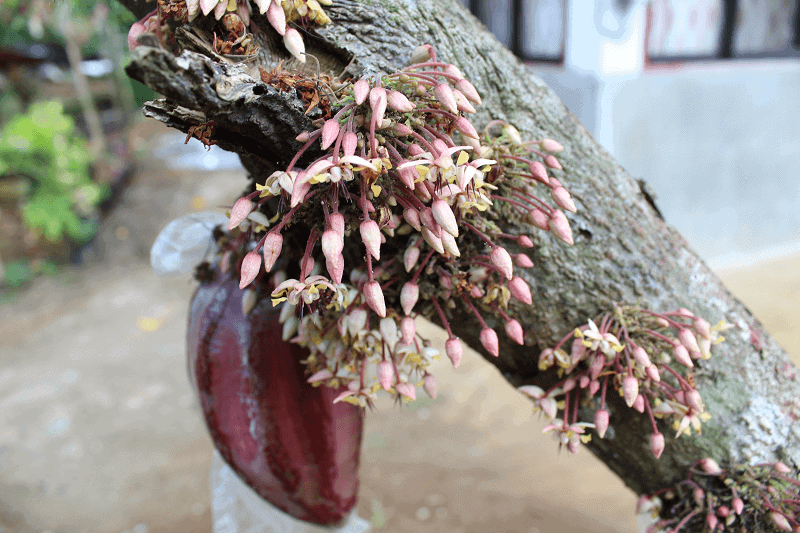

But even though cacao beans were exported to Spain, in a way the Spanish also imported something to the Philippines: consumption of chocolate. But unlike how we think of consuming a bar of chocolate today, the Spanish actually consumed chocolate in the form of a beverage, just as they learned form the Aztecs. In fact, criollo cacao seeds were brought over from Mexico, another Spanish colony at the time, and planted in Filipino soil.

This first successful tree sealed a Filipino-Mexican connection which persists into present-day, and which continued throughout the centuries in the form of the Galleon Trade. From the time when that first cacao was successfully cultivated on one of the islands of Luzon, local consumption has been growing. Those plantations watched over by Spanish friars also needed to use local people to conduct harvest, forcing cacao to become a part of their identity & history.

There's not a lot of information on when the general population of the Philippines began consuming cacao regularly. But even after their independence in 1946, they continued to lead the Asian market in cacao production for nearly half a century. And whenever the public did finally have access to it, they continued to consume it in the form of a drink. They created that drink from a combination of water and tableya.

Traditional Chocolate Production & Consumption

Tableya, more commonly spelled tablea, is basically a ball of ground-up, 100% cacao. The balls of cacao were traditionally processed using the Mexican metate method of grinding peeled cacao seeds between two stones until they formed a paste. The paste is then formed into balls and stored like that, untempered of course. When someone is ready to use the tableya to make hot chocolate, called sikwate, then one of those balls is added to boiling water and stirred rapidly until all of the same consistency.

The amount of water added said a lot about the amount of respect you had for the person to whom you were serving the beverage. In fact, if you were served sikwate at all, then you must have garnered great respect from the Catholic church, as they maintained power over cacao plantations until the end of their reign. To this day, tableya is still the primary form of cacao consumption across the Philippines.

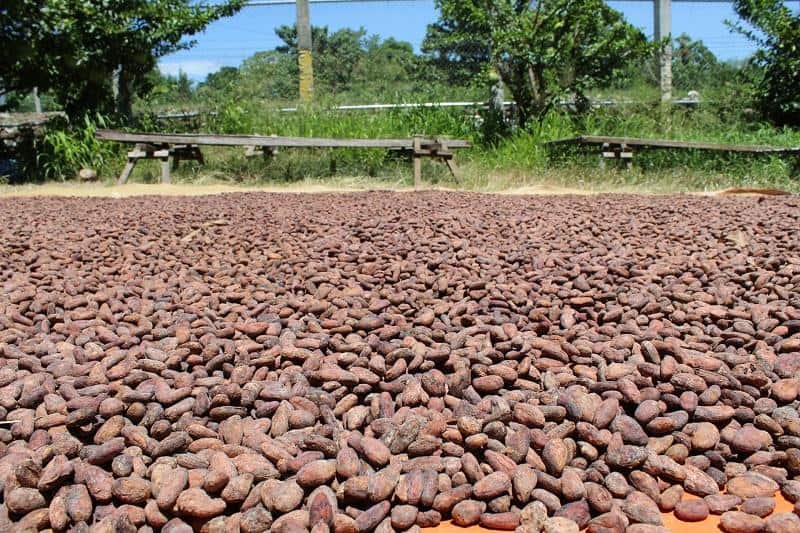

It used to be that Filipinos who had cacao trees in their yards would put the seeds out to dry in the sun, and then bring them to the nearest market, where a man would grind up their beans for a small fee. Then they could form it into balls at home (since the Philippines is so hot year-round, it stays relatively soft for awhile), and store them for future use. Unfortunately, with increased urbanization, having cacao trees in your yard isn't all that common anymore.

But still, in a way there's not much legacy of chocolate consumption in the Philippines, sort of like in nearby Hong Kong. You don't eat tableya in the sense that it's not a ball of chocolate. Since there's no sugar, that would be a very bitter bite indeed (though we've all tried a bite of the baking chocolate in our pantry, am I right?). And while there have certainly been mass-produced chocolates made in the Philippines before, it's seen as a very separate product from tableya. So chocolate consumption as most people might think of it isn't very popular in the Philippines. Tableya, on the other hand, is so popular that it's actually led to a cacao deficit in recent years.

The Cacao Industry In The Philippines

As stated earlier, best estimates of when cacao arrived on the Philippines is in the late 17th century, more specifically around 1670. Over the years, the cacao farms being watched over by friars changed hands numerous times, eventually ending up mostly as large plantations scattered across the islands. Notably the majority of those plantations are located in the region of Mindanao, the southernmost part of the country, and more specifically in Davao City.

Nearly 80% of the country's cacao is still grown in Mindanao, although that's slowly changing as farmers across the country begin to combat the recent downturn in cacao production & world cocoa prices. As the government's efforts at land redistribution have continued, many of the historically large cacao farms were broken up and redistributed to local landless people. Many of those new farmers in turn chose to cut down or ignore the cocoa already growing on the land, usually in favor of other seemingly more valuable crops.

This is only part of what led to the downturn starting in the 1980's. At the same time there were also high-producing varietals of cacao from Malaysia being planted across the country, in an effort to get more from less on these smaller plots of land. Many, though not all, replaced their ancient criollo trees with these newer varietals. At the same time, the Mars Chocolate Company was buying lots of Filipino cacao.

People from Mars even came down to many farmers in the highest-producing regions and taught them how they wanted the cacao they bought to be processed. Basically, this resulted in even more quickly-processed cacao with the least work put into it, and most importantly, the lowest possible priced paid to farmers. In turn, this lowered the farmers' own views of cacao as a cash crop.

There are hundreds of thousands of Filipino farmers who each have their own story of connection to cacao, some longer & more strongly-voiced than others. But how the Philippines got to this low point of cacao production is due to a combination of several factors, not all of which are under farmer control. Most important to note is the downturn of Filipino cocoa production in the 1980's, neighboring countries' growing cacao industries, and fluctuating prices of related crops, like coconut.

In reaction to renewed global interest in cacao production, recent governmental intervention has resulted in tens of millions of cacao seedlings being planted across the country. This is over the course of just a few years, too. The government's free distribution of these seedlings come as a result of their goal to increase national production tenfold compared to 2016 levels, reaching 10% of global market share over the next three years. Initially they'd hoped to reach these goals by 2020, but have since extended that deadline by two years, in light of how long it will take the distributed seedlings to bear fruit.

Changing Tides For Filipino Farmers

Very little of the Philippines' cacao has traditionally been fermented. To be fair, it didn't really need to be, as the majority of their cacao was of a criollo varietal from Mexico, and therefore naturally less bitter. But part of the government's efforts to increase cacao production include improving how and how much of the country's cacao is fermented.

Fermentation is one of the steps in chocolate making which develops many of the flavors we associate with chocolate. So the unfermented or under-fermented beans traditionally used for preparing tableya simply aren't suitable for chocolate-making. Neither, or the most part, are the beans processed using the techniques taught by the Mars company a few decades earlier.

So what can farmers do? Well, some will carry on how they always have and be perfectly content with minimal returns from their cacao, as Val from CIDAMI (Cacao Industry Development Association of Mindanao) has said. But for those who want to learn better post-harvest techniques in order to earn more from their cacao, there are now lots of resources available. CIDAMI runs workshops across the islands, and some farmers are now offering paid seminars on cacao production.

But the Philippines' recent cacao growth spurt isn't a direct reaction to the country's cacao deficit and a desire to lessen reliance upon imports. It's a strategic move on the part of the government, both federal and local, to ramp up production of crops which can be added to existing farmland. With cacao, it's both possible & beneficial to inter-crop trees with other common agricultural goods in the Philippines, such as coconuts. This intercropping increases the country's overall yields, brings more money to farmers, and contributes to reforestation.

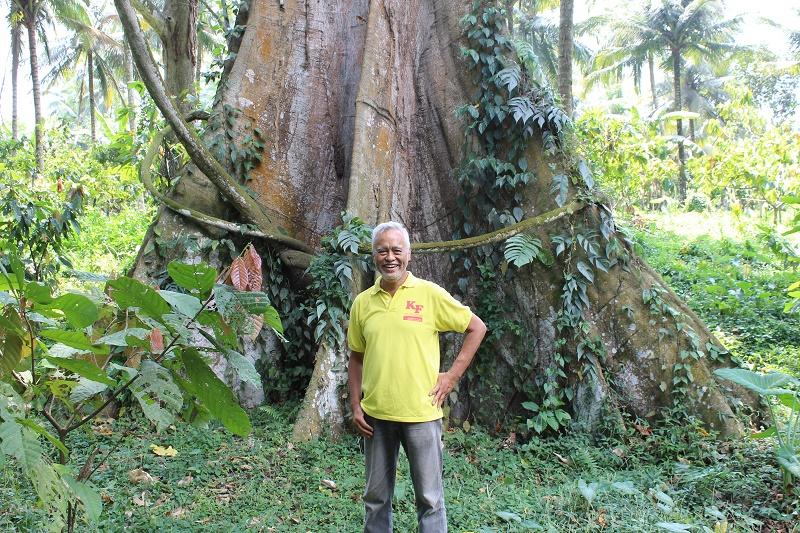

Additionally, these existing fruit trees are often also the perfect tree mother for baby cacao trees, offering shade from the harsh sun. With the increased popularity of local cooperatives, farmers also now have more opportunities to ferment smaller amounts of cacao more regularly, ensuring they only pick pods when ripe. Having increased availability of quality cacao will also bring more opportunities for farmers to add value to their crops. Some of them may even turn out to be the pioneers of Filipino chocolate culture.

Craft Chocolate In The Philippines

This movement towards Filipino craft chocolate has been in the works for years now. But it hasn't been a very easy sell to the local public. Filipinos associate cacao with tableya, not chocolate; for them it's not a natural progression from cacao to chocolate, as it is in many other cacao-growing countries. Cacao is a fruit made for drinking or sucking off the pulp, maybe even making a little cacao liquor.

But there are some fine chocolate makers who've been working hard to get the word out. While I can't name all the chocolate makers in the Philippines, there are a few who've had a disproportionate impact. Outside of the Philippines, Auro Chocolate is probably the country's most famous chocolate maker. They've done a great job at both working with local farmers and promoting their chocolate for local consumption (about four-fifths of their chocolate is purchased domestically).

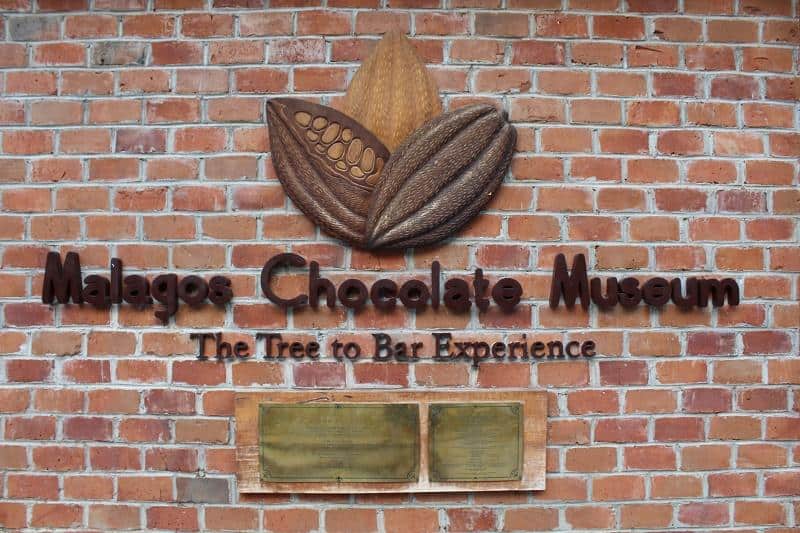

However, if you ask a Filipino about local fine chocolate, they'll most likely mention Malagos Chocolate. Often cited as one of the first tree-to-bar chocolate makers in the Philippines, Malagos uses cacao from their own huge farm in Davao City to make 100% Filipino dark chocolate. Their Gardens have become famous within the country, and recently they were even internationally-awarded. Malagos and Auro are both quite large companies, however, and I'd argue that the future of fine chocolate in the Philippines is small-scale.

Cacao Culture Farms in particular has arguably done a better job at getting their names out there on social media, networking with local farmers, and overall just making their presence known online. It's part of the reason I reached out to them about visiting Mindanao in the first place. Because even though their target market is Filipinos in the Philippines, if customers had to visit Davao City in order to pick up products, they'd be out of business really quickly.

The whole region of Mindanao has actually been under martial law for years, thanks to domestic terrorism in the southeast of the country. As I said, the attempt to completely Christianize the Philippines was NOT successful. But despite the terrorism (which is hundreds of miles from Davao City), small tableya- and chocolate-producers like Cacao Culture are definitely more the norm. And as more farmers become interested in adding value to their cacao crop, I also see it as a great way to keep Filipino cacao consumption truly Filipino.

The Future Of Filipino Chocolate & Cacao

It's slow going, but many Filipino farmers seem on-board with the addition of cacao production to their existing landscapes. Not all of them are doing it out of the goal of reforestation, but honestly, who's worried about the planet when you can't afford to feed your kids?

Once the millions of trees planted in the last few years begin finally producing, you can also expect to see literally tons more cacao available on the market. Hopefully much of this cacao will see value added at home rather than post-export.

This includes the making of high-end products like fine chocolates, cosmetics, and health foods, as well as transformations lower on the scale, like processing cacao beans into cocoa powder and cocoa butter. So while the future of Filipino chocolate is looking bright, the future of Filipino cocoa is on the up & up, as well.

A huge thanks to Ken & Sheila of Cacao Culture Farms, as well as Val of CIDAMI, and the manyother people I had the chance to interview and chat with as part of this story. Your insight into the Filipino cacao industry has been invaluable.

Joel

I tried to buy dark chocolate at Walter mart and they could only find one very expensive imported bar. With the hot here and the chocolate staying soft, I understand why people are not buying. Interested to know how you think this will change considering chocolate may not be refrigerated.

Max

I'm hoping that more people will be able to access the high-quality chocolates being made across the Philippines, from the far north of Luzon to as far south as General Santos (and this is just from my own travels). As the recession hits here in the US and Europe continues to deal with the war, I don't think rates of importing chocolates into the Philippines will be changing anytime soon, unfortunately.

Edgar Lanutan

I think the history of Philippine Cacao as written here and in many articles is not right.

Not possible for me to plant cacao in the Philippines out of seeds from Mexico, months after they were harvested. Cacao embryos will be DEAD.

I think, Philippines has our own indigenous cacao, but, we don't know them ang their use. Spanish has the knowledge and claimed our cacao as their cacao.

Max

That's simply false. Looking at the genetics of the plants, it's not physically possible that the Philippines spontaneously evolved its own Theobroma species several hundred years ago. From what I've read, it sounds like whole trees were brought over from Mexico and kept alive somehow on the ships, though it seems likely that very few such specimens would have survived, so it's more likely that several pods were kept moist enough to germinate and at least one of those germinated seeds survived... it only takes one, after all.

Graham Carey

Can you give me advice on reputable organoleptic testing and reporting organisations I could use for process improvement, please? I'm trying to set up a bean-to-bar operation in northern Thailand.

Max

Sorry, I'm not sure who the right people are to contact about that; I've never had to look into such testing. Maybe reach out to the guys over at Siamaya Chocolate in Chiang Mai?