Many people confuse the countries of Taiwan and China. Citizens of both places speak mostly Mandarin, and many share Chinese ancestry. But indigenous culture on Taiwan is not to be overlooked, accessible in the country's most prominent landmarks, like Taroko Gorge or Kenting National Park. Ask any Taiwanese person where they're from, and they'll introduce themselves as Taiwanese, not Chinese.

This is an important distinction, as it's part of the history which has formed Taiwan's cultural consciousness, influenced its agricultural past, and has the potential to impede any future expansion of its cacao industry. While China is huge, Taiwan is a relatively small island with both tropical and sub-tropical regions. Even for those traveling only in Taipei, it's probably going to be a hot trip. Winters in Taiwan are mild, and in the center and south it's warm enough to grow cacao & other tropical fruits, some of the best things to eat in Taiwan. Other than high quality tea, one of the favorite souvenirs to pick up in Taiwan are pineapple cakes and dried fruit slices.

Though as the Southeast Asian country continues to develop, farmers continue looking for more ways to add value to their crops, if not get out of the industry altogether. For Taiwan's young cacao industry, this spells trouble. Taiwanese people aren't known to consume much chocolate, unlike Americans, whose young cacao industry (in Hawaii and Puerto Rico) at least has a built-in market. Yet despite those obstacles, Taiwanese cacao farmers are going full steam ahead.

Jump To

How Cacao Came To Taiwan

To catch you up on how chocolate is even being made on Taiwan at all, let's take a trip southeast of the island. Cacao is native to the northern region of South America. It was first brought to Asia via the Philippines, thanks to colonizing Spaniards, and was first brought to Taiwan thanks to the colonizing Japanese. During Japan's 50-year colonization of Taiwan, there was at least one Japanese company growing cacao on the island, probably starting in the very early twentieth century.

Thanks to its tropical climate, central and southern Taiwan are suitable for growing tropical fruits such as cacao, mango, and pineapple. While the Japanese people were starting plantations on the Ilha Formosa, their government was also making a big push to grow sugar cane across the south. While the legacy of Taiwanese sugar cane well outlasted the end of the occupation, Taiwanese cacao was cut down and replaced with other crops after the end of World War II. There were no commercial ventures trying to grow cacao on Taiwan for decades afterwards.

Starting around the 1980's, there were several distinct attempts made to grow cacao on Taiwan. But in the grand scheme of tropical fruits, cacao requires a lot of input & extra effort compared to other crops like passion fruit or wax apple. Unlike most fruits, which are consumed in their whole state, cacao needs to be harvested when ripe, and then fermented and properly dried before it's ready to be made into chocolate.

To pay farmers for the extra time required to properly process cacao— not to mention the training needed to learn such skills— those beans needed to fetch a much higher price than the market was willing to pay at the time. So all those attempts just kind of waned out. Cacao wasn't really grown seriously on the island until the turn of the century. But how has Taiwan's growing cacao industry finally taken hold?

Adding Value To Taiwanese Cacao

In terms of commercial production, Taiwanese farmers are still largely unaware of the many steps needed for proper processing, though local buyers have been working on that. The main problem is still that the world market price is too low to make it worthwhile for farmers. The current market price for 1kg of high quality Taiwanese cacao is 600-1000NT (~$19-34USD), while 1kg imported from nearby Papua New Guinea might run a chocolate maker just 400NT ($14USD) after taxes and fees.

Unless consumers are willing to pay much more for chocolate made with Taiwanese cacao, farmers will soon run into a problem when trying to sell their cacao (for a living wage). Although demand is currently outstripping relatively meager supply, domestic and international interested in Taiwanese cacao won't continue unless quality stays consistently high. So many of those same farmers are turning to chocolate as a way to make a living.

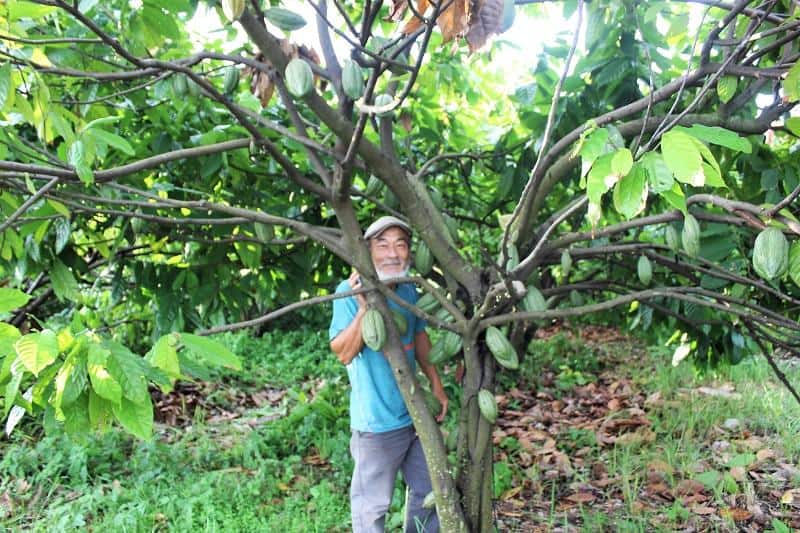

But the chocolate making process is complicated, and made even more so when you have full manipulation over all the ingredients. Yet for someone like Ming Song Chiu, that's also the interesting part of chocolate making; he can tweak the entire process for the Taiwanese palate with relative ease. At his restaurant and cafe, Choose Chiu's, Ming Song shows off the results of the efforts he and his entire family have put into turning Taiwanese cacao trees into Taiwanese chocolate. This has turned out to be the missing piece for many Taiwanese cacao farmers, the step which adds enough value to make their efforts worthwhile.

Making Tree To Bar Chocolate on Taiwan

Starting in 2007, the Chiu family was making tree to bar chocolate for the local market, slowly improving cacao processing and adding more sophisticated machinery to their tiny chocolate factory. Last year, their shop processed local cacao into over 400 tons of high percentage dark chocolate. While the Chius were the first to process their cacao into the finished product, many other local farmers have joined the movement towards value-adding local cacao. There are now regular chocolate making workshops for cacao farmers in Taiwan's southernmost growing region.

The efforts of other Pintung farmers have been well over a decade in the making, like Siong-Goan Lee's efforts to teach better post-harvest processing to local farmers. More recent evolution of these efforts include the formation of the Pingtung Cacao Farmers Association, buying fresh cacao pods from multiple farmers to ferment smaller amounts together. With proper processing, farmers can grow smaller amounts of cacao in addition to their existing crops, making it worth farmers' while to process smaller amounts as a cooperative without feeling the need to start their own chocolate brands.

Southern farmers have found great success in adding cacao trees to land where betel nut (areca palm) trees are already growing. The areca palms grow a seed which has long been chewed locally as a stimulant to continue work, similar to caffeine or nicotine. But the nut has been shown to cause oral cancer, and the Taiwanese government is anxious to discourage its growth across the south. This gives them great incentive to support the region's fledgling cacao industry through seminars and other educational initiatives.

Over the many years since the Chiu family began their farm-fresh chocolate making, the Taiwanese tree to bar movement has slowly spread northward as high as Taichung City. With international help from experts like Malaysia-based Eddie Kim and Japan-based Kanako Satsutani, farmers have been able to identify how various steps in processing change the final flavor of chocolate (for better or worse). The farmers are slowly mapping the mix of varietals on Taiwan and experimenting with new products, but outside of the Pingtung region, the island's chocolate education is slow going.

Chocolate Culture on Taiwan

While the number of bean to bar chocolate makers on Taiwan grows year after year— having at least doubled over the last 2 years— it's tough to say how much the local market has expanded. With many more bean to bar makers than tree to bar makers, particularly in Taipei, the focus on local agriculture is harder for consumers to pin down. The cost of craft chocolate is around three-to-five times more per gram than the bars you might find at a convenience store like xiao chi (7-11), so it's been tough for all makers to crack into the market.

The most popular chocolate brands in Taiwan come from Japan and China, and even the dark chocolates still usually contain lots of sugar, maybe 45-50%. So-called "black chocolate" bars, actually dark chocolate bars from Japan, are the most popular choice. Taiwanese people are very interested in the possibility of eating chocolate for health benefits, as has become popular in Hong Kong. This leaves a great opening for local chocolate makers, but whether people will be willing enough to pay for quality that it supports dozens of small-scale chocolate makers is a question only time can answer.

With existing tea culture, and the beginnings of coffee culture at the turn of the century, there's a long history of savoring local products in Taiwan. Just in the realm of black teas (actually red teas), central Taiwan produces several varietals and honors the history & nuance of each one. But even during the last two decades or so, local coffee has been slow to catch on. Local cacao seems to be following the same path, as a cultural import with great potential— as long as farmers can stay in the industry long enough to see that potential fulfilled.

Developing the local chocolate market has been a long-term pursuit for chocolate makers like the Chiu family, and Siong-Goan Lee's niece (Joyce), who keeps her chocolate cafe open on weekends to sell to locals. Otherwise, much of her chocolate is sent up to Taipei, where it's sold to northerners and a fair number of tourists. She runs chocolate making workshops for small groups, but there's not enough demand to keep them on a regular schedule.

Many tourists visit for a short time, and rarely leave the largest cities of Taipei, Taichung, and Kaohsiung. There the cost to open & maintain a chocolate shop is prohibitively high for most chocolate makers. So it's incredibly important for makers to focus on their local markets rather than export. In the southern part of the country this has meant embracing the concept of leisure farms, in which guests visit a working farm to see a condensed version of all the work that goes into growing their favorite products. Photo ops are a must.

A similar activity done often by chocolate makers, and even chocolatiers, are DIY workshops for kids. These do-it-yourself classes usually last about an hour, cost less than $10USD per head, and give solid background on how cacao is grown & chocolate is made. All of this happens while the kids are able to get their hands covered in chocolate, which is a win/win in my book. I think every other chocolate maker, theme park, and museum I visited had some kind of DIY class on offer; it's very much a part of the culture. While the kids learn, the parents do, too.

The Future of Taiwanese Cacao & Chocolate

The current landscape of adding value to cacao on Taiwan is almost exclusively in the form of experiential education and selling finished chocolate & cacao nibs. This increases the final price paid to the farmers/chocolate makers, as well as saving costs on shipping for retailers interested in selling Taiwan-made products. But for anyone looking to use Taiwanese cacao off the island, good luck. Taking advantage of the cacao liquor, pulp, and other cacao-related waste produced on the farm could be a possibility in the future, but for now the industry is still so young.

More cacao trees are being planted, but even those will take years to bear fruit. Focusing on strengthened relationships between cacao farmers and chocolate makers is a must if the value is to stay on Taiwan. And a value-added model has to be part of how the country builds up its cacao industry, otherwise it won't last very long. Keeping the farmers and their education at the center of this model is imperative. This goes for the consumers, as well.

Taiwanese farmers, as with all farmers, are business owners; even if they're very passionate about something, eventually they need to get paid. Their outlet for that is currently through Taiwanese chocolate brands like Choose Chiu's, FuWan Chocolate, and Funky Chocolate. Hopefully soon more chocolate brands will be able to incorporate other Taiwan-grown products, like dried fruits and vanilla beans (currently grown in Puli Township, an hour outside of Taichung).

Taiwan's burgeoning craft chocolate industry is providing hundreds of farmers with outlets for cacao grown at almost any scale, but this industry comes with its own issues. As Taiwanese chocolate makers and cacao farmers look into expanding their market outside of the country, they turn to international chocolate competitions to provide them with globally-recognized accolades. Certainly not every farmer or chocolate maker is applying for awards just for the sticker price-bump, but it was expressed to me as a particular issue in the south. And it makes sense.

Once you or your competitor applies for an wins an award, it puts pressure on you to win, as well. For farmers and makers alike this can add up to higher prices, but it's also an expensive endeavor in-and-of itself. An awards sticker may convince a consumer to buy in the first place, but it's quality which keeps them coming back.

Then again, sometimes that first purchase can make all the difference. Taiwanese people certainly know when to spend time & money on their own well-being, and with the potential to expand into nearby Hong Kong and all of China, that first purchase towards good health could add up to a lot of income for farmers and makers. Taiwanese chocolate is growing, but only time will tell if it's growing quickly enough to support its many farmers.

Comments

No Comments